Children who were conceived by women using fertility treatments do not show an increased risk for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), a large Danish population study reports.

The study, “Risk of juvenile idiopathic arthritis among children conceived after fertility treatment: a nationwide registry-based cohort study,” was published in the journal Human Reproduction.

Infertility affects about one in every six couples worldwide. As a result, the use of fertility treatments is increasing, with Denmark having one of the highest proportions of children born through the use of fertility treatments.

Several studies have reported an increased risk for adverse outcomes, such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and birth defects, in children born using fertility treatments compared with those conceived spontaneously.

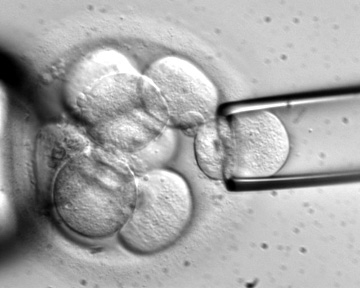

Fertility treatment — including hormonal stimulation with fertility medicines, and different chemical and mechanical procedures involved the process — can affect the development of the fetus’ immune system. Additionally, “it is also possible that underlying environmental, biological and genetic factors related both to infertility and JIA may affect the risk of JIA among children conceived to women with fertility problems,” the researchers wrote.

However, there is little information about the potential long-term effects of fertility treatments on a child conceived this way, including the risk for developing cancer, and mental or autoimmune disorders.

Therefore, a team of Danish researchers set out to investigate whether children conceived after fertility treatments have an increased risk of developing JIA.

The team performed a retrospective population-based study where they analyzed 1,084,184 children born alive in Denmark between January 1996 and December 2012. The children were followed from their date of birth until December 2014, or until they were first diagnosed with JIA, turned 16 years old, or were no longer able to be followed in the country (due to emigration or death).

The researchers linked the children’s clinical data with that of the Danish Infertility Cohort to identify those born from women with fertility problems and from women who underwent fertility treatment.

From the children evaluated, 83.9% (909,482 children) were born from fertile women. Women with fertility problems gave birth to 16.1% (174,702) of the children in the study, and 51.5% of those children were born from women who received fertility treatment, while the remaining 48.5% were born from women without any treatment.

The median follow-up was 10.3 years and during this time, 2,237 children were diagnosed with JIA at a median age of 6.3 years.

Children born from women with fertility problems had a slight increased risk of JIA (1.18 times higher) compared with those born from fertile women.

However, compared with children born from fertile women, children born from women using fertility treatments were at no higher risk for developing JIA. This risk remained unaffected even after accounting for different fertility treatments individually — assisted reproductive technology includes in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, or any fertility medicine.

Overall, while these results “indicate that children born to women with fertility problems may have a slightly increased risk of JIA,” the data suggests that “this increased risk is likely not due to the fertility treatment per se,” the researchers wrote.

This slightly increased risk may instead be explained “by underlying environmental, biological and genetic factors related both to infertility in the mother and JIA in the child,” they added.